The Richtersveld is a biodiverse, arid area in the Northern Cape Province of South Africa. In 2005, we camped in the National Park for several nights. A 4WD vehicle is essential. We would not have gained entry without it, as the approach road was a sea of mud following recent unseasonal rainfall. We passed a grader ineffectually working to extract a truck that had gone off the road and was stuck in the stuff. Later that day, I recall driving over uneven rock pavement at a steepish gradient, making that first day alone justify the expense of our capable rental. The vehicle had both good clearance and traction.

The attraction of the area for me was the possibility of finding unusual succulent plants. I grow lithops (stone plants) at home, and hoped to find some in their native habitat. Although we did not find lithops here, elsewhere in South Africa, nor in Namibia, which encompasses their native range, we saw a lot of different succulent plants, including other mesembryanthemums, in the Richtersveld. We were also lucky enough to see some in flower.

The scenery is magnificent. While we were visiting the park we saw few other people. There were a couple of groups camped at the De Hoop campground on the Orange River, but we had Kokerboomkloof to ourselves.

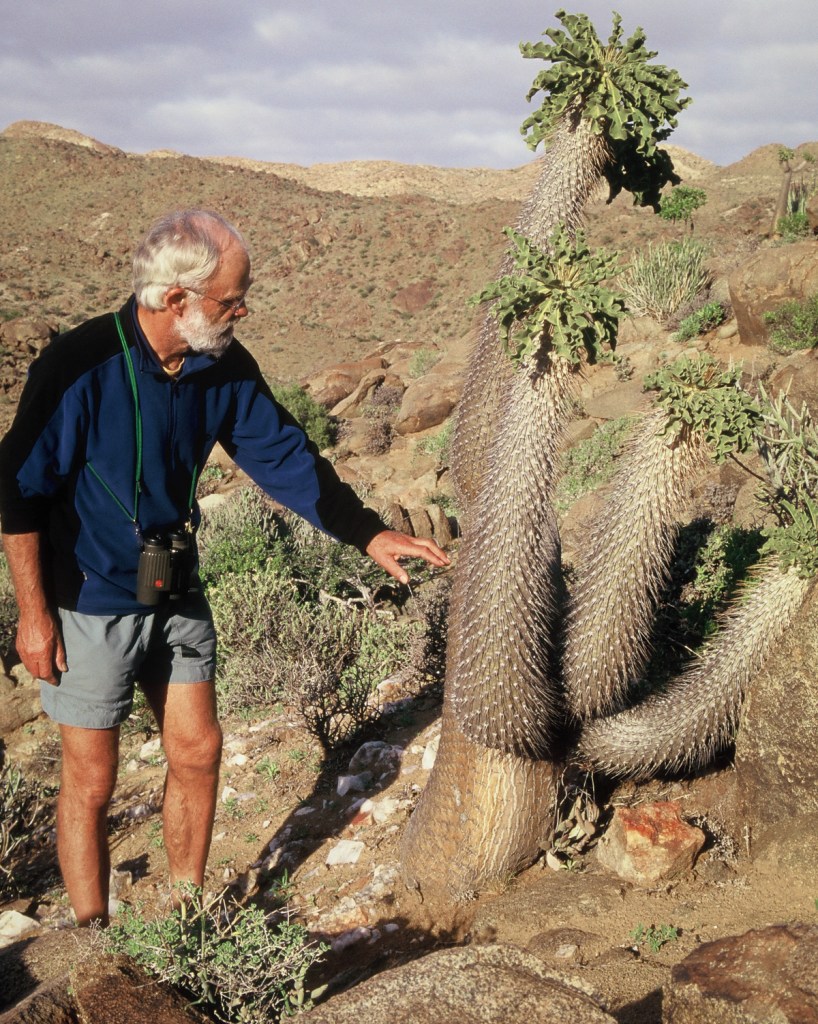

The kokerboom tree for which the kloof is named, is beautifully adapted to its desert habitat. Known also as the quiver tree, Aloidendron dichotomum is a succulent. It grows well in sandy and rocky soil, storing water in its thick trunk and leathery foliage.

Facilities in the campgrounds were basic. Kokerboomkloof had not water but clean rest room facilities that were tastefully designed to fit in with the environment.

The roads are 4WD tracks, but easily negotiable in dry conditions. The area feels remote and even hostile, although it supports a diverse range of plants and small animals.

This buprestid beetle (they are known as jewel beetles) is a wood borer in its larval stage. We did not see a lot of animal life. Many of the creatures of the desert are nocturnal, allowing them to avoid the desiccating heat of the scorching midday sun. In many protected areas of South Africa driving at night is not permitted. I think this may have been true in the Richtersveld. In any case, we restricted our activities to daylight hours.

The succulent plants were spectacular. Many of them, including Pachypodium namaquanum, are slow growing, so we felt as if we were in an ancient forest.

The diversity was very high for such a harsh environment. I had already been amazed at the immense variety of plants in the Cape Region, which is classed as a biodiversity hotspot. The survival of so many species in a small area relies on a complex web on plant-animal interactions, including specialist pollinators and parasites.

The scenery was out of this world. I am always attracted to exposed rock that reveals the bones of the landscape. To me, a desert landscape offers both raw beauty of landform and interesting plants that inspire awe for their tenacity in the face of the harshest of conditions. A single flower on one of these plants may be the culmination of years of mere survival.

As individuals we are insignificant in the world. As a species were are devastatingly influential. Hopefully areas such as the Richtersveld will be preserved for future generations to appreciate.