Lying on shore, seals look indolent. Reminiscent of lions that seem to spend more of their time lounging in the shade. However, seals spend lots of time actively swimming after food, especially when feeding pups, and earn their rest.

I began using an infrared camera to photograph landscapes. This is Balanced Rock in Arches National Park, Utah. I like the way the treatment lightens vegetation, sometimes giving an otherworldly look, which I find especially appropriate for cemeteries. I use a black and white conversion, for good contrast.

Then I began experimenting with animals, and liked what I got. This is a male mule deer in South Dakota. The grasses take on a delicate backdrop against which the animal stands out clearly.

This chipmunk, caught in mid-leap, again stands out against a pale and blurred background.

This next images was not intended to be in infrared. On that day, at Sheep Lake, in Rocky Mountain National Park, I saw a moose feeding, and needed my telephoto lens. The only camera I had with me at the time was the infrared converted OM Systems OM1, so I used it. Again, I liked what I got, the dark animal standing out against the light-coloured vegetation, and a tiny duck on the opposite edge of the frame.

I will experiment some more. I do love trees as well as animals, and using a lens baby with the infrared camera gave me this:

The tree is in Longmont, Colorado, and area that before European settlement would have been extensive prairie devoid of trees.

Prairie dogs seemed extra wary in the campground at Santa Rosa Lake State Park in New Mexico. It was perhaps obvious why they were nervous when I spotted a pair of burrowing owls flying around the colony. Burrowing owls are very distinctive, with their small stature and long legs. Like prairie dogs, they inhabit generally flat, dry areas with only low vegetation. They nest and roost in burrows, often frequenting those excavated by prairie dogs. These small animals also serve as prey.

Unlike other owls, burrowing owls are often out during the day, although they tend to hunt mostly at dawn and dusk. I was out fairly early in the morning, having no idea that the prairie dog colony was here. Nor did I expect to see the owls. I’ve spent a lot of time scouring prairie dog colonies for these owls, often without success. This is the first time I’ve spotted the owls before seeing a prairie dog.

Safety in numbers ensures that prairie dogs survive, but they need to be vigilant. The least cautious individuals will end up as a meal for burrowing owls or coyotes.

Prairie dogs live in underground burrows in usually large colonies. They are welcome food items for coyotes and other predators. These images were obtained in Wind Cave National Park, in Wyoming.

This adult prairie dog with youngster is sitting upright in characteristic sentinel mode. Facing in opposite directions, the pair have the field covered. Often, prairie dogs will sit atop mounds of soil for better visibility.

I was lucky to spot this coyote on the chase for a meal. I first saw it loping along the side of the road, so followed in the car. There was no one else about. It crossed the road, then went down into a dip. I missed the actual catch, but when the coyote came back into view, its prey was in its mouth. The black tail of this species of prairie dog is diagnostic.

Another activity to watch, was this individual collecting nesting material to take down into the burrow. It is hard to imagine that there is room for a single additional straw in the mouth of this prairie dog. I was impressed that it could hold so much.

The Richtersveld is a biodiverse, arid area in the Northern Cape Province of South Africa. In 2005, we camped in the National Park for several nights. A 4WD vehicle is essential. We would not have gained entry without it, as the approach road was a sea of mud following recent unseasonal rainfall. We passed a grader ineffectually working to extract a truck that had gone off the road and was stuck in the stuff. Later that day, I recall driving over uneven rock pavement at a steepish gradient, making that first day alone justify the expense of our capable rental. The vehicle had both good clearance and traction.

The attraction of the area for me was the possibility of finding unusual succulent plants. I grow lithops (stone plants) at home, and hoped to find some in their native habitat. Although we did not find lithops here, elsewhere in South Africa, nor in Namibia, which encompasses their native range, we saw a lot of different succulent plants, including other mesembryanthemums, in the Richtersveld. We were also lucky enough to see some in flower.

The scenery is magnificent. While we were visiting the park we saw few other people. There were a couple of groups camped at the De Hoop campground on the Orange River, but we had Kokerboomkloof to ourselves.

The kokerboom tree for which the kloof is named, is beautifully adapted to its desert habitat. Known also as the quiver tree, Aloidendron dichotomum is a succulent. It grows well in sandy and rocky soil, storing water in its thick trunk and leathery foliage.

Facilities in the campgrounds were basic. Kokerboomkloof had not water but clean rest room facilities that were tastefully designed to fit in with the environment.

The roads are 4WD tracks, but easily negotiable in dry conditions. The area feels remote and even hostile, although it supports a diverse range of plants and small animals.

This buprestid beetle (they are known as jewel beetles) is a wood borer in its larval stage. We did not see a lot of animal life. Many of the creatures of the desert are nocturnal, allowing them to avoid the desiccating heat of the scorching midday sun. In many protected areas of South Africa driving at night is not permitted. I think this may have been true in the Richtersveld. In any case, we restricted our activities to daylight hours.

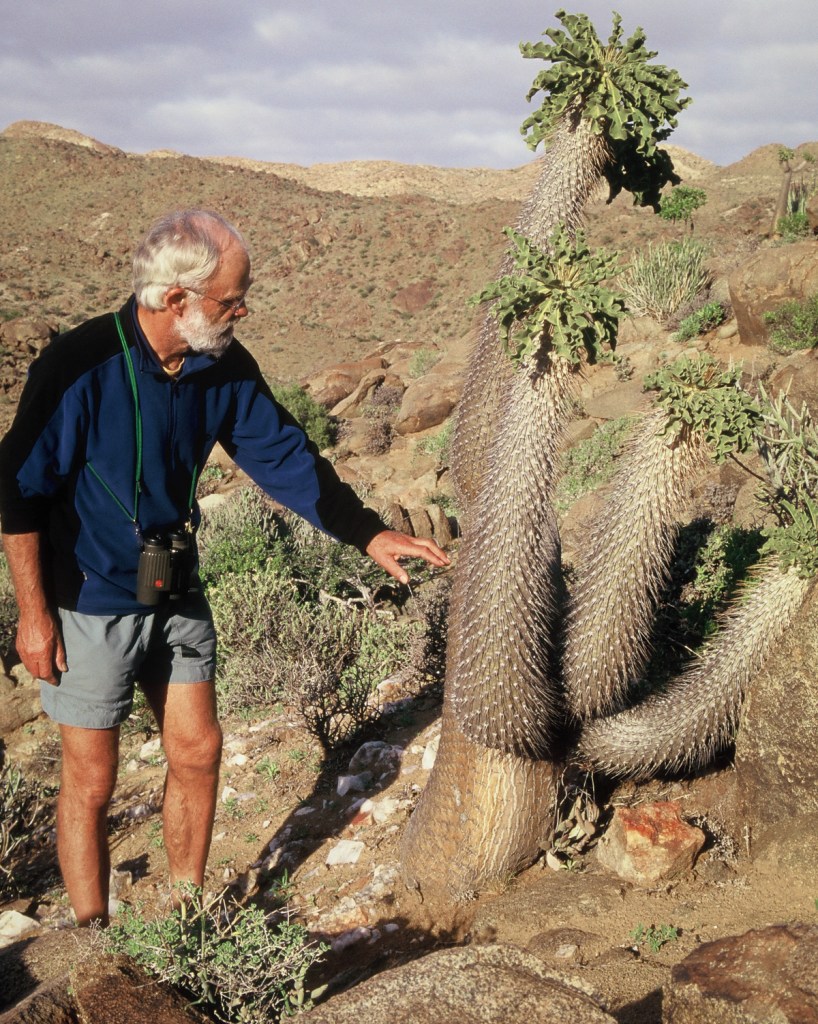

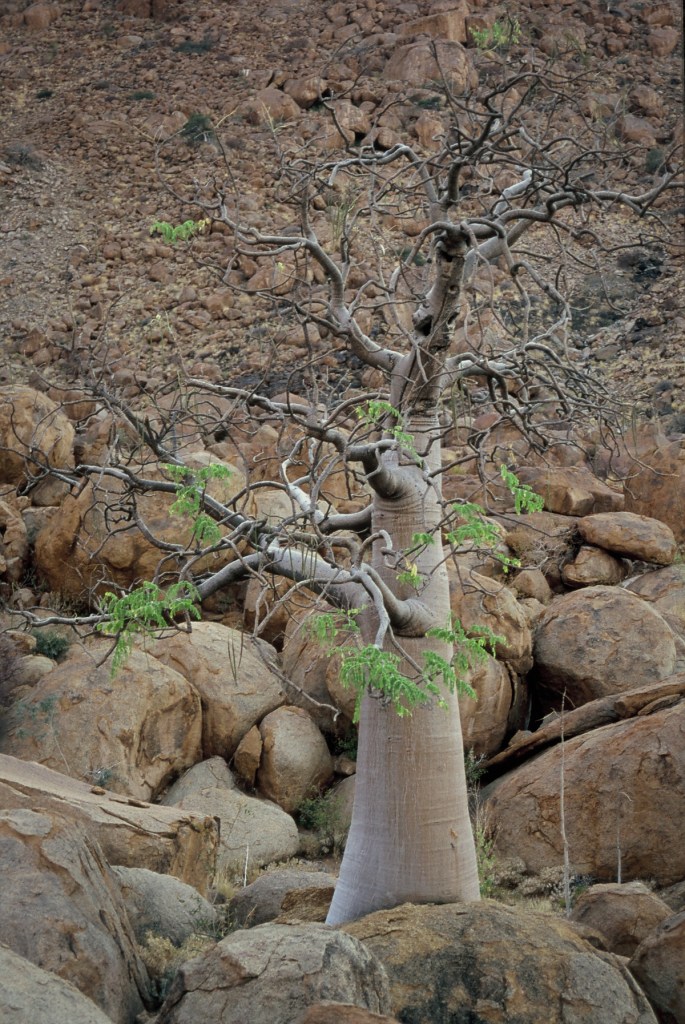

The succulent plants were spectacular. Many of them, including Pachypodium namaquanum, are slow growing, so we felt as if we were in an ancient forest.

The diversity was very high for such a harsh environment. I had already been amazed at the immense variety of plants in the Cape Region, which is classed as a biodiversity hotspot. The survival of so many species in a small area relies on a complex web on plant-animal interactions, including specialist pollinators and parasites.

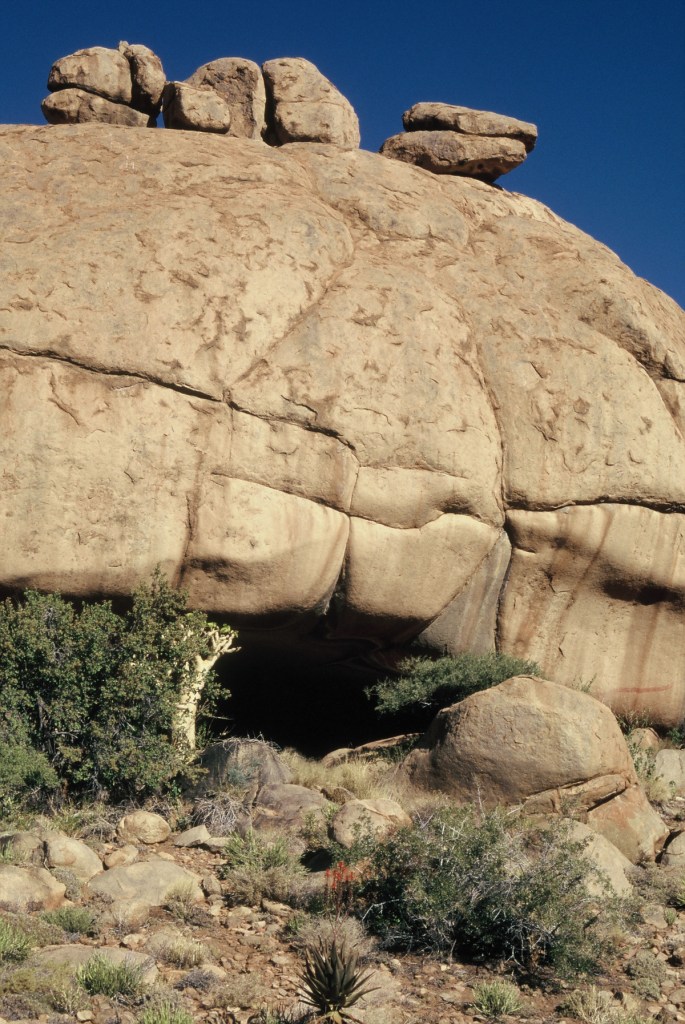

The scenery was out of this world. I am always attracted to exposed rock that reveals the bones of the landscape. To me, a desert landscape offers both raw beauty of landform and interesting plants that inspire awe for their tenacity in the face of the harshest of conditions. A single flower on one of these plants may be the culmination of years of mere survival.

As individuals we are insignificant in the world. As a species were are devastatingly influential. Hopefully areas such as the Richtersveld will be preserved for future generations to appreciate.

It requires a lot of energy to grow a rigid trunk that will allow a plant to outcompete its neighbours and capture the light it desperately needs to survive. The clever strategy adopted by climbing plants is to use these neighbours for support. Or maybe, as for this pretty, probably introduced member of the Convolvulaceae (Ipomoea indica) the climber gets a leg up using a human-built structure like this fence.

The Norfolk Island pine, with its straight, strong trunk, provides an effective ladder for I. indica. Solomon’s sinew, or wild wisteria (Callerya australis) is a native climber that also uses the Norfolk Island pine for support. The photograph below was taken in the Botanic Gardens. The prolific foliage of the climber gathers all the energy it needs to develop thick, strong vines to maintain a structure supported by the host trees.

Walking beneath the canopy, the vigour of Solomon’s sinew and other climbing plants is apparent from the thick vines that have developed through capturing the sun’s energy from high in the canopy of their host tree. When eventually the host tree dies and falls over, the vine sends out creeping stems to find another tree.

I wondered why these tangles of vines seem to be more common in tropical forests. Probably there are multiple factors. The trees grow faster than in temperate areas, so there is more incentive for other plants to use their structures to gain access to their height. The canopy is often dense, so understory plants have little access to sunlight essential for photosynthesis. Early accounts of the exploration of Norfolk Island tell of it being covered by impenetrable, thick forest.

I have enjoyed spending sufficient time here to explore beneath the surface. Having inadvertently left my colour camera at home, my focus has shifted from bird photography to examining the forest more closely. It is hard to imagine how Norfolk Island appeared to the first Europeans to discover it, Captain James Cook and his crew in 1774. Earlier Polynesian visitors had barely ventured inland from Emily Bay, so left the interior mostly untouched. European and Pitcairn Island settlers cleared much of the land, including felling all the largest trees, so that exotic species could be planted and farmland established. Introduced weeds thrived in the newly created environment. Nevertheless, the National Park (which includes the older Botanic Garden) was set up in 1984 to preserve and restore the original habitat. It provides an experience that will increasingly resemble the original forest as it might have been prior to settlement.

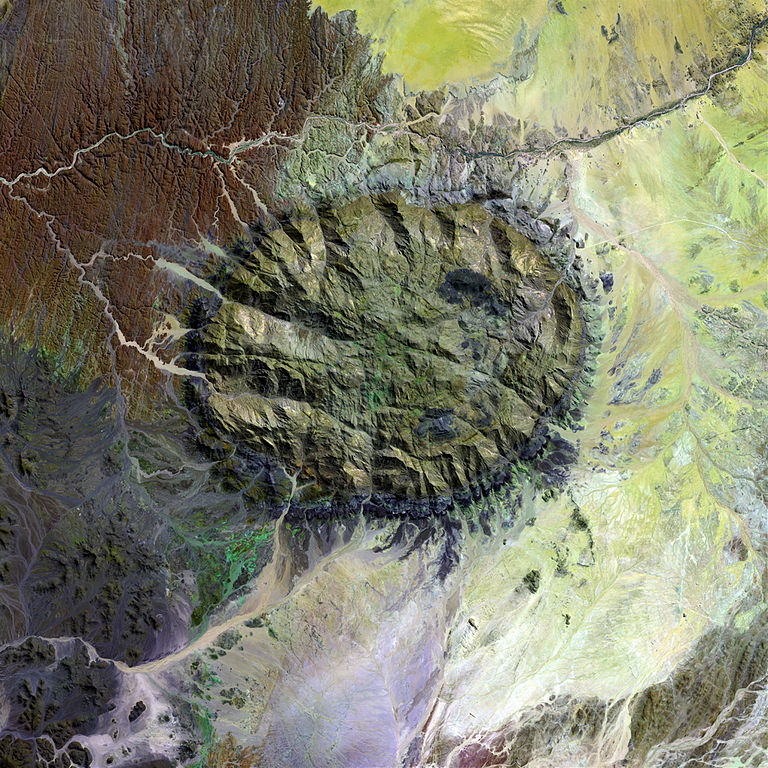

Brandberg (burning mountain), the highest point in Namibia, was surprisingly little visited as recently as 2005. This was when I had the chance to explore some of the 650-square-kilometre plateau which erupts nearly two thousand metres above the surrounding desert. It is a two day walk from the nearest road, and there is very little water up there. From about five thousand years ago until late in the nineteenth century a few San people made their home here, but now only crumbling ruins of rock dwellings and many thousands of rock paintings recall their passing.

Our expedition was one of those fortuitous events that comes together through friendships forged in interesting circumstances. Rowan and I first visited Namibia in 1991, just one year after the country gained independence from South Africa. That was an amazing experience in itself. There were few tourists. South Africans, for whom Namibia was their holiday playground, stayed away, fearing that things might have changed under the new government. International visitors had not yet found this magic place. We discovered that camping facilities were excellent, just as in South Africa, and everything worked very well. Brandberg attracted us, but we could explore only around its base as we didn’t have the knowledge or resources to access the plateau.

However, though my work in biological control of weeds, I got to know Stefan Neser, a biocontrol scientist from Pretoria and an outstanding naturalist. I talked with him and his wife, Ottilie, about going back to Namibia and maybe climbing Brandberg. Ottie followed up our idea and arranged for a group of relatives and colleagues to accompany us. Ottie’s cousin, Erica (an artist), and her husband Neerthling, an entomologist running a pest control business (also an expert on large mammals) joined us as well as Michael, another entomologist from Pretoria and Tharina, a spider expert from Windhoek, the capital of Namibia.

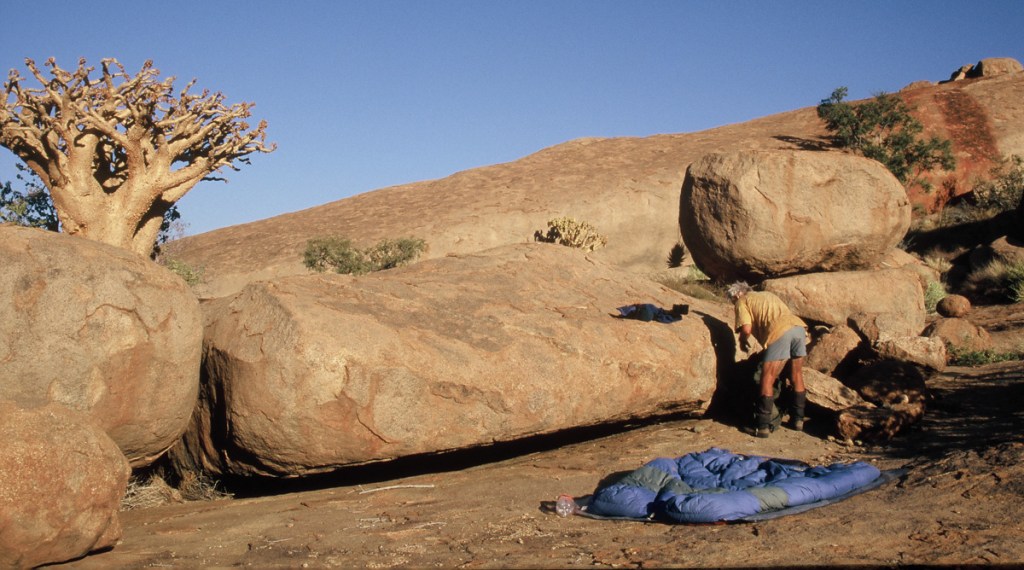

We drove to the base of the mountain in two rugged, high clearance vehicles belonging to expedition members. Ottie had a rough sketch map of our route that she had obtained from climbing friends and Tharina knew the route reasonably well as she had been here before. The camp spot they had chosen for us was at Longipoolies, one of few possibilities with access to water. Rainfall is sparse, but when it occurs, runoff is rapid as the rocky plateau holds almost no soil. At Longipoolies, fast flowing water has worn deep potholes in the rock which retain fresh water that we were able to use while camping there.

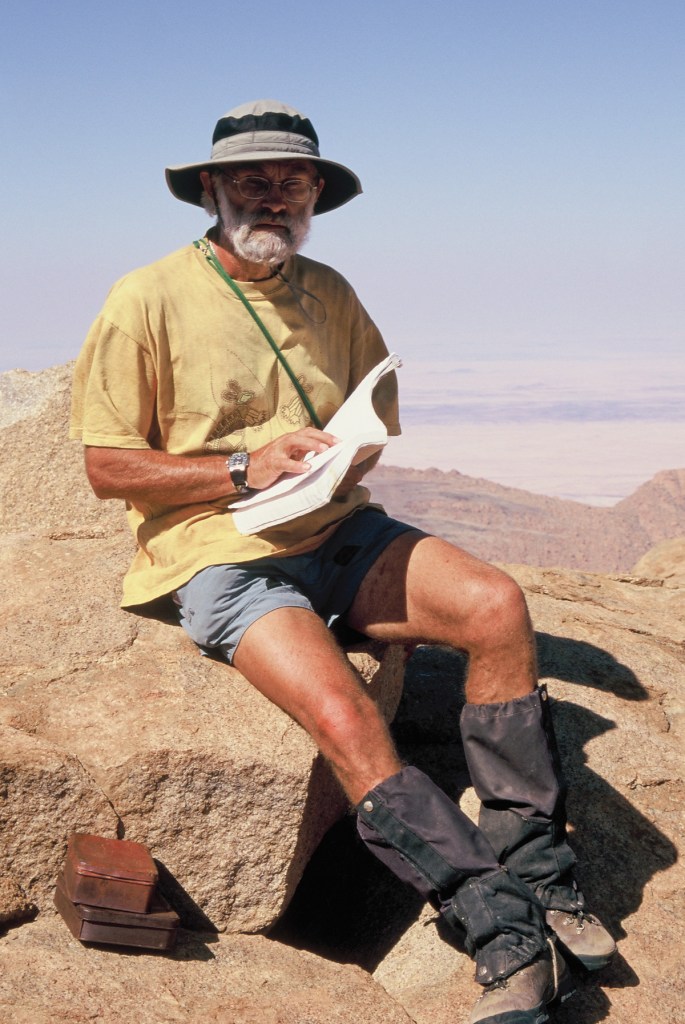

Our group of biologists had several days to explore the area. We hiked to Orabes Kopp through granite country traversing slabs of varying angles, scrambling over huge boulders, and following fissures between rock walls that sometimes became so narrow we were forced to retreat and climb a wall instead. Along the way, we noted and photographed unfamiliar plants and poked into cracks and crevices for signs of life. In that way it was easy to spend the entire day getting there. Views over the Namib desert were spectacular as Orabes Kopp lies near the edge of the plateau.

Another day, we headed to Konigstein, the highest point, and consequently the most popular destination, with a faint trail heading towards it. The trail passes the now famous Snake Cave, which is decorated with some of the finest aboriginal rock art that I have ever seen. The view from the summit revealed the intricate nature of the plateau: rocky peaks, narrow valleys and undulating slopes creating diverse habitats for hardy life forms that survive on little water.

Michael went home with some mosquito larvae, the first ever to be recorded from Brandberg, as well as other unusual flies. Tharina found a diversity of neat spiders and Erica made some lovely sketches. Stefan photographed many rare plants. On our last night, lying in our sleeping bags stretched out on the warm, smooth granite, and gazing up at the bright stars overhead, I fully intended to return one day to explore more of this amazing place.

I’ve been scanning some old slides, and picking out a few that interest me. The image above is a wet black backed jackal in Kruger National Park. I like it because it is the only time I’ve seen a jackal out in the rain with its coat looking wet and bedraggled. The plains and deserts where animals are easiest to see generally have low rainfall. In addition, the dry season is often the best time. to visit because animals tend to be concentrated near waterholes, so easier to find. The next few images are from Etosha National Park in Namibia: zebra, a young springbok, and a spotted hyena.

The last two were also photographed in Kruger: a red hartebeest and a male elephant:

There are healthy populations of the New Zealand fur seal (Arctocephalus forsteri) all around the coast of the South Island, as well as a few that are establishing along North Island coasts. Seals have been steadily increasing in numbers since being fully protected in the 1950’s and as by-catch during fisheries operations has been reduced. The species is also found in Australia. Unlike leopard seals, which are found on sandy beaches, fur seals prefer rocky shores. Ohau Point on the Kaikoura Coast, is an excellent place to see them.

Rocky outcrops off Ohau Point

The native ice plant, Dysphyma australe, grows in rock crevices.

There is now an extensive lookout area with good parking that has been developed since the road was severely damaged during the 2016 Kaikoura earthquake. As almost the entire coastal section of the road had to be rebuilt, it was an opportunity to increase the quality of visitor experience along this wild coastline. All these images were made from points along the walkway.

Seals are still unpopular with some fishermen, and subject to occasional bouts of abuse. However, as city dwellers increasingly appreciate nature, seals are valued by many citizens, especially when wildlife comes to town. They often join forces to protect seals from dogs when they haul out on popular beaches. The Department of Conservation has provided signage that volunteers can put out to alert dog walkers of the presence of seals. Sorry, I didn’t think to take photos when I accompanied a friend to put signs around a seal on Sumner Beach, in Christchurch. If it happens again, I’ll try to rectify this! There are more seal images from Ohau Point to follow.